Word X

This is a word puzzle game that I designed for the new iPhone X. Since the iPhone X has a completely different look and feel compared to previous iOS, creating this project was a pleasurable experience. There is a minimal approach as the app holds the main game board and a reverse button for the placement of words. Technologies Used: Sketch, Adobe InDesign, and Principle.

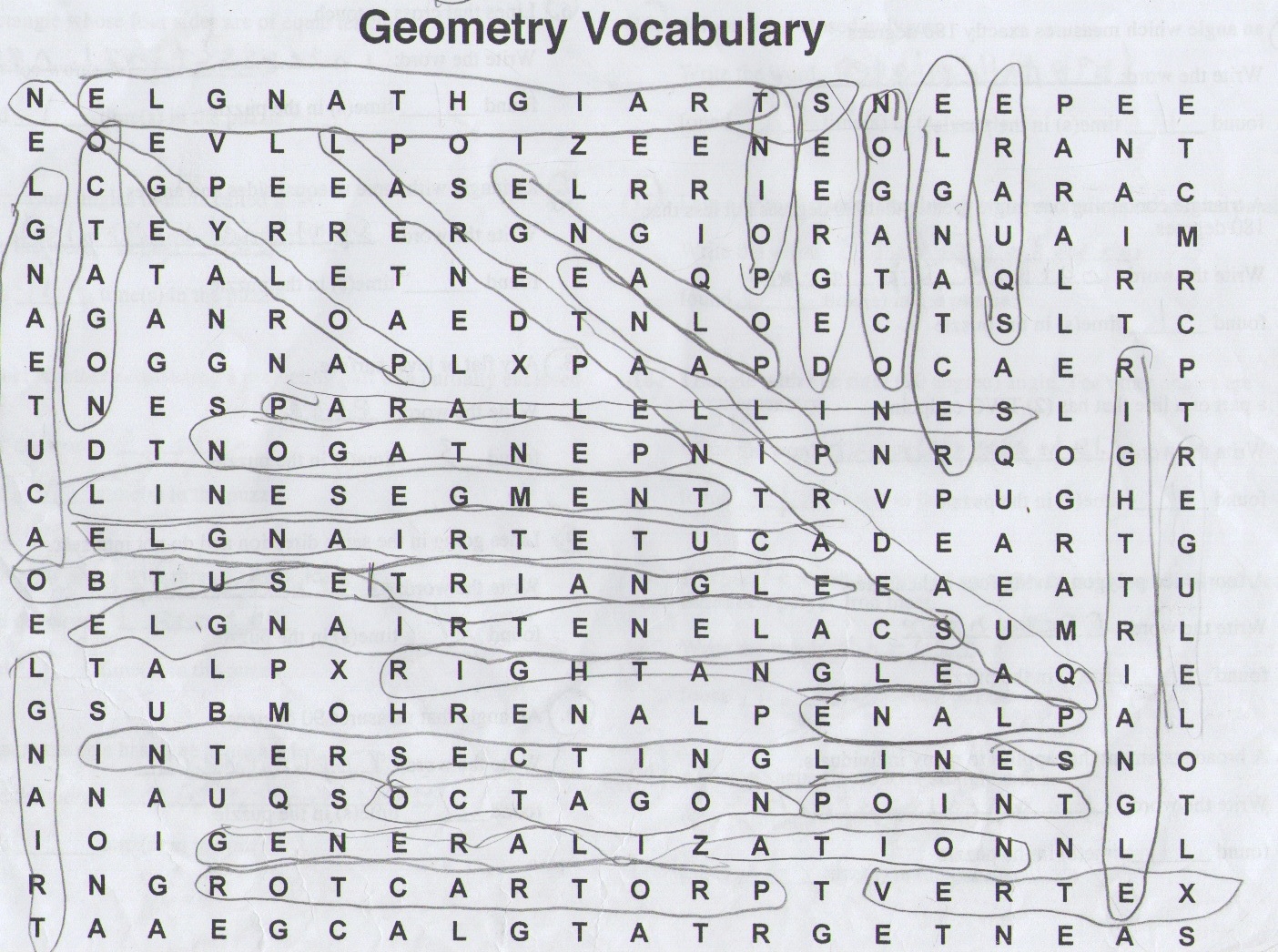

My game mockup

The state of word games

I’m making a fun little word game for iOS. In the process, I’ve done some research and some me-search: what is the state of word games, and why do they interest me?

Here’s what I’ve discovered so far.

0. Puzzles and Me

I am 7. Sunday mornings go like this:

Dad and I make the waffles. Mom slices the fruit. We eat. Mom and Dad drink coffee. I drink milk. We clear plates. We retreat to the living room. Mom puts on some music. Dad reclines on the couch. I sit on the rug. Mom and Dad work on the Sunday magazine crossword puzzle in concentrated silence. I entertain myself somehow.

I am 10. I start “helping” Dad with Puns & Anagrams and the acrostic, when he lets me. On special occasions I construct crosswords for my parents. They are broken and unsolvable, but warmly received.

I am an adult. (!?) Every two weeks Dad scans the acrostic from the Sunday magazine and emails it to me. I love the acrostic. I don’t do other puzzles.

This is all to say: I have a long relationship with crosswords. The relationship is lightweight but steady. I am not obsessed but I understand the obsession. The way crossword puzzles have inserted themselves into the everyday (or every-other-weekend) lives of millions of people is fascinating to me.

One of the first crosswords published in the New York Times Magazine

1. Crosswords and History

A brief history:

The first crossword appeared sometime in the late 19th century, possibly 1862, in the United States. Crossword puzzles became popular in the 1920s. The New York Times refused to print them, calling it a “sinful waste,” a “primitive form of mental exercise,” and a “dying fad.” In 1942 they relent and begin publishing what becomes the most celebrated crossword puzzle in the world.

So, crossword puzzles are a recent invention. Their history more closely resembles Candy Crush than it does chess (developed in India in the 3rd century). At 150 years old, they occupy a strange space in games. They’ve got staying power, sure. But they’re not necessarily here to stay — maybe when my parents’ generation dies out, so too will crosswords. Crosswords are kind of like watches. They might evolve, might fade away, are unlikely to remain unchanged.

2. The Business Model

The crossword economy consists of 3 parties: constructors, solvers, and publishers. Publishers pay constructors to construct puzzles. Solvers pay publishers, either for a publication that contains puzzles (eg., the New York Times) or for a publication that consists entirely of puzzles (eg., Mega Crossword Puzzle Book #4).

The success of these publications, particularly of the second type, suggests that the business model should work, Ben Tausig argues persuasively that it’s broken:

The financial stakes of the crossword are higher than a casual solver might realize. The New York Times, which runs the most prestigious American crossword series, pays $200 for a daily or $1,000 for a Sunday, which is certainly more generous than its competitors. However, The Times also makes piles of money from its puzzles. Standalone, online subscriptions to the crossword cost $40 a year ($20 for those who already subscribe to the dead-tree edition of the paper). In this 2010 interview, Will Shortz, the paper’s famed puzzle master, estimated the number of online-only subscribers at around 50,000, which translates to $2 million annually.

Meanwhile, The Times buys all rights to the puzzles, allowing them to republish work in an endless series of compendiums like The New York Times Light and Easy Crossword Puzzles. In that same interview, Shortz called these “about the best-selling crossword books in the country.” All royalties go to the New York Times Company, the constructor having signed away — as is the industry standard — all of his or her rights.

It’s unclear whether “crossword constructor” is a viable standalone profession, or should be. But it is clear that constructors should be paid more, likely through some kind of percentage of royalties.

Whether they are paid well or not, constructors will continue to construct. They do it for the love of the game.

3. Family Resemblances

Shifting gears.

What makes a word game a word game? What makes a puzzle a puzzle? What makes a game a game?

The crossword is the archetypical word game. The Acrostic, the Diagramless, Puns & Anagrams, Split Decisions are its cousins. Scrabble and Boggle are word games, but of a very different sort. Word search is a lowbrow word game, the black sheep of the word game family.

My old puzzle from elementary school

What about Sudoku? KenKen? These games don’t have words at all and yet feel closely related to Crosswords. What’s going on here?

Two points here:

- The family of word games is rapidly growing. It is fertile. KenKen and Sudoku are recent inventions that had the rapid ascension — but not the rapid decline — that we associate with mobile games.

- Family resemblances aid momentum. KenKen succeeded in part because it looks like Sudoku, which succeeded in part because it looks like and sits next to the crossword. Looks matter.

4. Aesthetics

The area of gameplay that is available on large screen is minimal when held in portrait mode.

iPhone X makes UI design easy—because all there is no UI

The UI disappears, there is no need for faint lines, small arrows, tiny text.

UI on iPhone X is should be as invisible as the iPhone itself, the content should be the main interaction point.

In this respect text as a button — something Windows Phone innovated on, is a interesting new UI pattern for the iPhone X.

What Apple understands is that by removing the edge of the screen you need to remove the UI at the same time, and by doing so the content needs to work harder then ever to convey the actions the user should take next.

5. The future

I started with this idea: What would it look like if mobile word games were done right?

It turns out many mobile word games are doing it right. A few I’ve been particularly impressed with: Words with Friends, WordHack, SpellTower, Word Shift, Letterpress.

The makers of these games don’t seem exclusively — or even particularly — interested in word games, which is a shame, because I think there’s an opportunity to build a family of word games that people play for decades. The manual for doing this seems to be:

- Make your game part of an everyday ritual

- Create a familiar aesthetic that gives new games momentum

- Establish a business model that attracts constructors

I guess these 3 steps are obvious and could apply to just about any mobile game studio. But the optimist in me says that slingshotting birds or rearranging candy is less durable than playing with language.